Nuance is coming to a paywall near you

Publishers are getting more sophisticated in how they gate their content

A song to read by: “He’s an Indian Cowboy in the Rodeo,” by Buffy Sainte-Marie

What I’m reading: “The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is,” by Justin E. H. Smith

Editor’s Note: Yes, I have switched back to Substack after a year on Ghost. No, I do not want to talk about it.

Just last week, some of the more irrational types among us began proclaiming the death of digital subscriptions was nigh — pointing to the demise of CNN+, the decline of Netflix and the glasnost at Quartz, this false prophet was trying to deliver the good sheep of the publishing industry into the clutches of despair.

Here at Medialyte, where we mull ponderously over every development in the media world before issuing such hasty proclamations, we know, in fact, the opposite to be true. Rather than fading away, digital subscriptions are instead evolving.

As the ever prescient folks at Toolkits point out, digital subscriptions and the paywalls that undergird them cannot fail to work — they are a business model, not a teaching assistant in an intro to philosophy course.

It helps, rather, to think of a subscription product as an equation, where only the correct inputs will result in the desired output. If a publisher creates a digital subscription program and it fails to gain traction, then they have miscalculated some element of the equation and must adjust it. As always, this sounds much easier than it is.

What are the elements of this equation? There are at least a half dozen companies whose entire business aims to answer that question, which is how you know it has a lucrative solution. Some of the obvious components include: the price, the strictness and type of paywall, the nature and volume of content, the subscription pipeline and the copy and design used to promote the subscription.

There are certainly dozens of other variables that publishers can tweak to fine-tune their subscription product, and the savviest media companies are constantly running A/B tests to do just that. But one element, of late, has become the object of intense debate, and that is the type of paywall.

We all know what paywalls are — they are the annoying pop-ups that prevent you from reading stories that you want to read. I think I can speak for all of us, the collective readers of the world, when I say paywalls are loathsome and I wish they had never been invented. But until the day the capitalist world order finally crumbles, I am afraid that we are stuck in the regrettable position of having to pay for the things we value.

So, below, in what I can only stimulating refer to as a taxonomy of paywalls, is a breakdown of the various kinds of paywalls, who uses them, why they use them and how they work.

Hopefully this family tree will help you realize how surprisingly diverse the world of paywalls is, and why that bodes well for an industry that is astoundingly varied itself. With such an array of options at their disposal, every publisher should be able to find — or develop — a kind of paywall that matches their content, readership and mission. That would mark a small step, but an important one, in making media a tiny bit more sustainable.

The below list is likely incomplete — please holler at me with paywalls I have overlooked — and it moves from least to most restricted.

No paywall

What it is: Self-explanatory

Who uses it: Axios, Protocol, Nieman Lab, Vox, Mother Jones, The 19th

Why they use it: Assuming a media company has made the intentional decision to eschew a paywall, publishers that let their content hang loose generally do so for one of two reasons. First, they are a mission-based organization, like a nonprofit, and they want their reporting to be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay. Second, they produce general-interest content that has a wide appeal, allowing them to, in theory, generate enough advertising revenue to stay afloat without making people pay to read it.

What Mark thinks about it: As a reader, I love it. As someone who reports on the business of media companies, this is far harder to pull off than most people think. You need a massive — and still, paradoxically, valuable — audience to make these numbers work with the pennies that digital advertising pays.

Digital publishers do have more advertising vehicles than ever before — think newsletters, podcasts, events — and that could enable more outfits to make the free plan work. But conventional wisdom holds that even if you can cut it without implementing a paywall, why not at least offer a premium tier to give your super fans a way to go deeper? We’ll get to that in a second.

Guilt paywall

What it is: A pop up, which you can easily close, that tells you how many articles you have read and prompts you to donate if you have found the publisher helpful

Who uses it: The Guardian

Why they use it: The Guardian has an endowment that helps subsidize its operations, making it a kind of quasi-nonprofit. It wants everyone to be able to read for free, but it also wants to offer readers a way they can support the paper. Plus, readers who donate, a.k.a. members, get access to exclusive content. (It should be noted that The Guardian, in the last month, announced that it has begun seriously considering deploying a paywall, a big deal in the industry.)

What Mark thinks about it: The guilt paywall is a brilliant case study: It straddles the line between the mission-based model of a nonprofit, which implores people to donate because they believe in the cause, and an actual paywall. It makes an emotional appeal to readers for support and it concretely demonstrates the value you, as a reader, have found in its reporting. But I have never donated, so …

Registration wall

What it is: You have to provide your email address to read an article

Who uses it: Quartz, Toolkits

Why they use it: For most publishers, getting someone to hand over their email address means you can begin sending them newsletters, a noncommittal way to develop their habit of reading your writing. (Can you imagine?)

At Quartz, they believe their newsletters are their most effective way to convert a reader into a subscriber, so rather than hit fly-by readers with paywalls, they usher you onto their email list and let it work its magic.

But publishers of all stripes, including big ones like The New York Times, are increasingly requiring that readers fork over their email and create an account to access their reporting. That way, the publisher can get you reading their emails and begin to create a profile of you based on your reading habits, which enables them to more accurately advertise to you. Publishers are fearful of inserting this point of friction in front of first-time readers, but changes to digital privacy laws could soon make it far more commonplace.

(I am counting the strategy of The Times as different from publishers, like Quartz, who have no paywall but require an email. The Times will ask you to subscribe an article or two after they get your email.)

What Mark thinks about it: I dislike being added to email lists involuntarily, but I understand the logic. In this situation, I will provide my email and then make a mental note to unsubscribe when the ensuing email arrives, a tiny act of labor on my part but one I generally resent. And I never forget.

Archival paywall or timewall

What it is: Content is free for a period of time, then goes behind a paywall — or the opposite: Content is paywalled, but then becomes free when it reaches a certain age

Who uses it: BoiseDev, Adweek

Why they use it: For BoiseDev, which gave paying members early access to new articles, the idea was to incentivize membership — it was a perk that still kept the content accessible. Adweek gates all content that is more than two weeks old, which increases the value of a subscription while keeping new material open to the masses.

What Mark thinks about it: The BoiseDev strategy seemed like a smart innovation, but one that will likely only work as an add-on. For Adweek, I love it — it’s a remix of the freemium model that makes a lot of sense. Speaking of …

Freemium paywall

What it is: Some content is paywalled, some is not — generally based on the type or article

Who uses it: USA Today, Digiday

Why they use it: Jack Marshall at Toolkits thinks freemium models might be the future, and I am inclined to hedge my bets until the truth surfaces and then pretend I knew it all along.

With freemium models, publishers can choose which content to paywall and which to keep free, allowing their broadly appealing material to act as a top-of-funnel device and their paywalled content as on-site marketing for their subscription product. Freemium offers a clean, clear distinction between the two tiers, and it allows publishers to monetize all of its readers — readers are never turned away, only enticed to go deeper.

What Mark thinks about it: Smart, understandable, effective! My only note: I think the ratio of gated to ungated content needs to be heavily skewed, like 80-20. If I am paying for a subscription and see that the bulk of what I am paying for is available for free, I start to reconsider how valuable that 20% is.

Subject-specific paywall

What it is: A specific subject matter or vertical is free — or the opposite: everything is paywalled except for a certain vertical

Who uses it: Bloomberg, Insider

Why they use it: Bloomberg keeps its Bloomberg Equality and City Lab sections free, despite the stiff paywall that guards the rest of the website. Equality is a mission-based project and keeping it free aligns with the spirit of the endeavor. City Lab is a wonky property that Bloomberg acquired, and its imported audience is unlikely to pay for a subscription.

Insider, on the other hand, splits its content very broadly by subject matter, where the light stuff brings in the audiences and the hard stuff gets them to convert, in theory.

What Mark thinks about it: The more free content, the better. Keeping certain verticals open, or opening them open in times of great need (early Covid, weather crises, etc.) builds a lot of goodwill with readers and serves a marketing purpose. These kinds of focused teasers, if kept tightly managed, can strengthen brand identity and attract new audiences.

Metered paywall

What it is: You get a fixed number of articles before the paywall hits

Who uses it: Texas Monthly, Bloomberg, The New Yorker, New York Magazine, The Atlantic, The New York Times — this is probably the most ubiquitous paywall

Why they use it: Metered paywalls are very popular because they make intuitive sense and are easy to implement. They allow readers to familiarize themselves a bit with the product and for publishers to monetize those visits, while still ensuring readers hit the paywall or at least know it is coming.

What Mark thinks about it: These are the workhorses of the digital subscriptions economy! They are a relatively blunt instrument, which is why some publishers see them as a jumping-off point, but they are effective and require little day-to-day management. Still, they can encourage readers to game the system, reading their two articles a month and then dipping, a problem that also applies to the paywall below.

Dynamic paywall

What it is: An algorithmically applied paywall that assesses factors like how recently you visited, how many articles you read and what kind of content you read

Who uses it: Rolling Stone

Why they use it: It is theoretically more individualized than a metered paywall. For people who would never subscribe, they never see a paywall; for people who are likely subscribers, they will see a paywall. Publishers are always wringing their hands over presenting various cohorts of readers with the right options for that kind of reader. This is the current apotheosis of that line of thinking.

What Mark thinks about it: I think they are unintuitive and could confuse readers, and they generally lead me to game the system (avoid a website for months, then binge on articles). I also generally distrust algorithms when it comes to making decisions that flirt so closely with editorial judgment. But, I appreciate their logic and understand that they are the only product that can make these kinds of person-by-person distinctions at scale. Jury is out!

Hard paywall

What it is: No content until you have subscribed

Who uses it: The Information, The Fine Print, DebtWire

Why they use it: If you write incredibly in-depth articles that are highly valuable to a niche readership, you might be able to get away with an absolute paywall. The main challenge is that people get no opportunity to see the content before deciding to pay for it, and subscribing to something sight-unseen requires a level of financial vulnerability that makes most people balk.

What Mark thinks about it: These kinds of paywalls are often expensive, meaning they are essentially business expenses. This model makes no sense for general consumers, but if your reporting serves an affluent, competitive industry, you can go straight for the corporate account.

Some Good Readin’

— Quartz was just got acquired by G/O Media. (New York Times)

— I spoke with Luke Winkie about BuzzFeed Inc. and its decision to go public. (Nieman Lab)

— The best take on Musk buying Twitter so far. (Platformer)

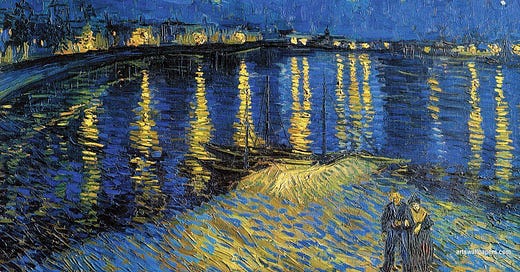

Cover image: "Starry Night Over the Rhône," by Vincent van Gogh